An article is based on scientific research, brought to you in a simple way.

It is long known that there are some neurological differences between the autistic brain and the non-autistic brain. These differences tell how signals are processed differently in both.

Research has shown that one of the most significant neurological differences between autistic and non-autistic people is found in the condition of the amygdala. Other areas of the brain show differences too, but the amygdala stands out and is able to explain a lot about the dynamics of autism in which anxiety often plays a vast role.

Some amygdala basics

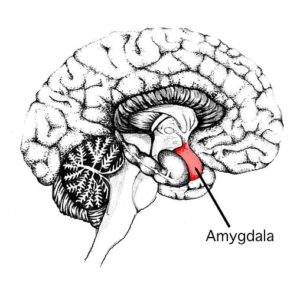

The amygdalae are two small almond shaped sets of neurons tucked away within the temporal lobe of our brain.

The amygdalae are two small almond shaped sets of neurons tucked away within the temporal lobe of our brain.

Our amygdala is one of the oldest parts of our brain that governs our most primordial instincts that are designed for keeping us alive, safe and that makes us procreate.

The amygdala records everything that is going on around us while it stores happenings of emotional impact as crude memories. Those emotional memories summon us to survivalist actions by fighting and flighting or freezing. It is all about survival of the species so it also drives another survival instinct, namely our sexual interests and impulses. The neurons of our amygdala also play an important role in our social behavior (which is also a survival instinct) and eating and drinking.

Sensory processing

To do its survival task the amygdala filters out all unimportant sensory information. It marks it as “neutral” so that that kind of information can pass through without any responses. The amygdala stays neutral when nothing is out of the ordinary while it starts to respond when meaningful stimuli arise.

For example. We are constantly surrounded by signals that can be safely filtered out. The clock ticks, the fridge buzzes, the neighbor walks, a tap drips, a door squeaks, a car passes by. Most are ignored by our amygdala while some others have a high priority, like for example the sound of breaking glass. Hearing such a sudden and unexpected sound puts us immediately in a state of instant alertness. It is the amygdala’s job to sort those signals out and make us respond strongly to danger, pleasure and nutrition.

In a way our amygdala can be seen as a switch board that ignores unnecessary calls while it puts all the high priority calls through to other parts of the brain. Like this the amygdala instantly relays every smell, sight, taste, sound and touch that we experience. The memory of a previous happening puts the call through to other parts of the brain before conscious assessment of the situation can arise.

Amygdala reflexes

Another part of our survival instinct is made of reflexes. Some are deeply rooted like sexuality and nutrition, while others are automatic reactions that are triggered by previous experiences. Those latter responses are very particular to our personalities.

Every intense experience is saved in us for future reference and is triggered when certain referential criteria are met. If particular intense situations are repeated then our responses become stronger (often leaving traumas). Our amygdala responses can also change. They can get weaker when the repetition seizes or when the situation becomes replaced by a new strong emotional imprint.

When at a later point a more or less similar situation occurs, then those past experiences are immediately revived by association. They react instantly, even before any thought can come up in our mind. This mechanism of the amygdala is switched on when some situation or person gives us a spontaneous reflex of love, disgust, happiness, distress, joy, anger, anxiety or frustration. We often don’t know why but it is there anyway.

The amygdala processes a lot of information and decides within 20 milliseconds how to act before any information is relayed to other parts of our brain, while it takes our conscious brain 300 milliseconds to become aware of the triggering event.

The mental trigger is not the only one that the amygdala governs. It is also capable of instantly triggering a flood of positive or stressful hormones in our system. The amygdala can also startle our nervous system with a shock, change our heart rate, change our breathing pattern, our muscle tension, our body temperature, and blood pressure and so on… This all is put in motion before we are aware for what, who or why all of that happens. All for not to die.

The social antenna

Another survival feature of the amygdala is its fluent social skill. The social aspect of the amygdala is a later evolutionary addition to it. It is the part that recognizes that social cooperation is essential for survival, while social disharmonies are a danger for it.

Its social skill is pretty amazing. The amygdala automatically reads and interprets pupil dilations, eye contractions, facial expressions and body language. It tells whether what is seen is safe or not. By these automated responses the amygdala also knows how to respond fluently to social cues that have been automatically learned before. This social antenna is a spontaneous response system that is based on deep rooted survival instincts and previous experiences. In safe social situations the amygdala triggers cooperating responses, while it triggers fight or flight responses when social danger is sensed.

Amygdala in people with autism

People with autism have an abnormal amygdala. For instance, autistic babies have 11% more neurons in their amygdala than non-autistic babies, while autistic adults have 20% fewer neurons than non-autistic adults. Another physiological difference is signal blocking lesions (damage) to the amygdala of an autistic person that is caused by an inflammation of the amygdala.

Inflammation

As we just discussed the non-autistic amygdala filters which signal to let through and which one not while the autistic amygdala doesn’t filter and lets all signals through (apart from social cues). This means that the amygdala in a person with autism is always on high alert and very aware of everything that is going on in the surroundings. The tap dripping is not filtered, neither the neighbor walking, or a car passing by, or a smell of perfume, it is all constantly there and therefore constantly overwhelming.

To the person with autism the intensity of this state of high alertness can vary. On good days and in good periods the autistic person can handle more while in other periods the autistic person can handle much less and can be overwhelmed with the slightest.

The reason for these different days or periods has to do with an inflammation that happens to the amygdala and to other essential parts of the brain. It is a bit like our skin when it is inflamed. When we have for example a sun burn then our skin becomes hyper sensitive and every touch is felt in an amplified way. In a very similar way an inflamed amygdala amplifies every sensory experience, that is thereby felt with a higher intensity that is related to the severity of the inflammation.

This inflammation is mainly caused by anxiety. The higher the anxiety level the stronger the inflammation while the inflammation reduces when anxiety levels reduce. Its mechanism is interesting.

We all have antibodies that constantly keep inflammations from occurring to our amygdala, other brain parts and also to our gut. It is easy to imagine that when these antibodies are deactivated that the inflammation can spread like a wildfire.

This inflammation is the result of an out-of-control immune response in autistic people.

When anxiety floods the autistic person, then his or her body is namely filled with hormones that deactivate antibodies that usually fight off inflammation of the amygdala. The lack of these inflammation-blocking antibodies causes amygdala and other parts of the brain and body to become inflamed.

The stronger the anxiety – the higher the level of these hormones – the stronger the deactivation of the antibodies that are supposed to fight the inflammation – the more severe the inflammation.

What is interesting to note is that most people with autism also suffer from gut problems that are related to the same out-of-control immune response. Most recognize that anxiety and stress worsen the condition of the gut which is then also an indicator of the state of inflammation that the amygdala is in.

This inflammation can be so severe the hypersensitivity can lead to shut downs or meltdowns. Over time stress and anxiety also causes lesions around the inflamed regions, causing a more permanent kind of damage to the amygdala.

Lesions

The lesions on the amygdala distort the signals that are transmitted by other people’s emotional states. This means that those signals only arrive partially in other parts of the brain. These lesions block the ability to registers pupil dilation, eye contractions, and certain areas of people’s faces that show emotional expressions.

These lesions don’t only respond to visual cues but also distort the understanding of voice changes and the comprehension of what certain kinds of physical stimuli like for example touches mean.

This kind of mind-blindness causes a retarded comprehension of the more complex emotional cues of others, which can lead to misunderstandings and unexpected responses.

These lesions are also responsible for hypersexuality or hyposexuality and other less standard sexual responses. They are also responsible for eating or wearing the same thing over and over again and cause autistic individuals to feel safer with familiar circumstances.

The (not so) social amygdala

These lesions inhibit the autistic persons ability to interact socially fluently. He or she has no standard comprehension of what socially normal or abnormal because what the mind is blind to it can’t see and what it doesn’t see it can’t learn. But the autistic brain has a failsafe to compensate the lack of this social mechanism. Other parts of the brain take over where the amygdala is dropping the signal. The subconscious mind of a non-autistic person usually does all the work effortlessly, while the autistic person has to sift through all information semiconsciously or consciously before responding. This makes the autistic person usually slow in social responses and often quickly exhausted by social situations and typically bad at small talk. An exception is when the person with autism is on familiar grounds with familiar people that he or she feels comfortable with. He or she performs well when the situation is totally safe and familiar.

What often creates an additional handicap for a person with autism is that it is hard to focus on a conversation when the environment is distracting. Noises, lights, movements, touches and so on can put the amygdala in such a high alert to everything that is going on around, that much of the conversation, no matter how interesting, gets blurred by the overwhelming environment.

There is another factor that often plays a big part in the social handicap of the person with autism and that is the factor of social anxiety. When someone never has been socially fluent then the amygdala will carry the memory from all those moments and have a signal ready that tells that social situations are unsafe. This causes anxiety for social situations until a lot of social training makes the autistic person feel more safe.

As we saw before stress and anxiety cause the amygdala to be more sensitive and to get overwhelmed. This also breaks down the ability of verbal communication by which the autistic person is often losing the capability to find the right words. This “selective mutism” often worsens the stress-loop which in turn worsens the ability to verbalize.

This hypersensitive stress tends to bring on an anxiety that freezes the autistic person up in unfamiliar social situations. Most autistic people have then the tendency to look for the first available exit while the flight-option that the amygdala also offers gets triggered.

The multitasking amygdala

No brain multitasks very well. It’s found to be only 40% effective. But the autistic brain isn’t able multitask at all because the amygdala is overwhelmed by the high amount of information. It can however function well and deep when it focusses on one thing. But when a flurry of different signals enters simultaneously, then the filing order gets confused which can cause great stress, exhaustion, shutdowns and even meltdowns.

When more than one factor is presented at the same time or when too many factors are brought up in a very short time span then the autistic brain can’t process those that fast and gets lost in confusion. The amygdala that does the automated filtering in non-autistic people is being bypassed in autistic people which makes it hard work. In one-on-one situations this kind of multitasking or fast-tasking can cause misunderstandings because the autistic person has a hard time to focus and to pay attention which can cause a shutdown or meltdown, while in more public situations this usually causes the person to drift off while not paying attention at all.

Sudden changes of focus during a conversation can cause a lot of stress and anxiety to a person with autism because every switch has to be made consciously. Sudden changes that are intense can also cause shutdowns and meltdowns because without an adequate reference to a topic the autistic brain is reference-less and lost.

The melt down and the shutdown of the amygdala

As we saw before the autistic brain can easily become caught up in detrimental stress loops. Stress causes an inflammation of the amygdala which causes a heightened sensitivity, while the heightened sensitivity of the amygdala causes more stress.

When a person with autism is caught in a stress loop then amygdala only knows three basic survival responses, namely “fight” or “flight” (when there still seems to be a way out) or “freezing up” (when there is no way out).

In fight and flight mode all senses and responses of the person with autism are focused on getting out of the perilous situation either by engaging or by retreating. When they engage then they often react with bad responses to a poorly understood situation. When retreating the autistic person can use very sudden and unconventional (and often unpopular) tactics to escape the situation that causes him or her to be overwhelmed by anxiety.

When an autistic person freezes up, then he or she is in a state of shock where his or her system is basically “shutdown” When the person with autism is in a state of shutdown then his or her brain is paralyzed and no longer able to understand the situation, which usually causes a great inescapable anxiety. The outsider usually believes that the person with autism is overreacting to a situation but for the autistic persons faulty amygdala the terror is very real and should not be underestimated.

A meltdown is basically a shutdown combined with a severe panic attack.

The main reason of shutdowns and meltdowns is the stress loop that also causes the amygdala to hyper-focus on what’s unclear, difficult or confusing, which maximizes confusions, which creates more stress until a point of ultimate terror is reached. When that point of ultimate terror is reached then we often speak of a meltdown.

The sequence of most meltdowns comes in 5 phases.

1 fight or flight

2 freezing up

3 numbness/ confusion

4 hypersensitivity

5 recovery

After the peak of the melt down the autistic person feels usually numb at first and then exhausted and extra sensitive for a period until normal balance is restored.

What physically happens is that during a meltdown the amygdala becomes so strongly inflamed that its sensitivity becomes unbearable, which makes the automatic response system go from “high alert” to “shutting down all systems”. Then light and sounds and touches become so intense, that the body responds to them as if it in an excruciating pain.

There are some signals that tell that a possible meltdown is coming up. When the amygdala is in the starting phase of melting down then usually understanding becomes foggy and speech difficult, in the next phase all understanding and speech fails while the autistic person experiences an overwhelming sea of impulses in which all overview is lost. Another signal is when the autistic person suddenly starts to stim very strongly. Stimming is a specific behavior that can include hand-flapping, rocking, spinning, or a repetition of words and phrases.

It is possible for the autistic person to avoid a meltdown or to pull the autistic person out of a meltdown by interrupting the cause immediately after it is recognized. Someone else can help the person with autism immensely by taking him or her to a safe spot, turning off sounds and light, or stop a stressful conversation topic when some of these signals are detected. Giving such care will already help the autistic person to feel safe so that he or she can relax. Hugs and touches are usually too much, but being present and caring can save the person with autism from a terrifying experience.

A meltdown (which is basically a breakdown of the functioning of the amygdala) is so excruciating that every person with autism deeply fears them and wishes to avoid them. Most autistics don’t know how to avoid them because of the “anxiety induced inflammatory response” that is spiralling out of control.

When the stress becomes a distress then the distress can become so unbearable that the inflamed amygdala overloads to the point of a seizure. At that moment the autistic person undergoes a terrifying brain-death in which everything normally reasonable stops working so that no normal responses can be expected. What is worst for a person with autism is to be blamed and pressured and told off for his or her behavior while he or she is melting down. Those are responses that only increases the panic attack and deepens the melt down. The only thing that helps in such a situation is a resilience to the reactions while one practices patience and care. What is maybe most important is not to take a shutdown or meltdown personally. It is always the reaction on many circumstantial factors of which usually none is personal.

Care and self-care (taming the amygdala)

The amygdala of an autistic person has a lot to endure. Sounds are always louder for an autistic person, light and smells stronger and touches are more intense. An autistic person misses the filter that makes all unimportant sensory information neutral. This is often experienced as a curse, but it is also a blessing in disguise.

Self-care for an autistic person is to make space every day for special interests and activities that are enjoyed. It helps the amygdala to focus away from all external information and filter only that what it can absorb linearly by zooming in on one thing only. It creates a space in which stress reduces and the inflammatory response can reduce. Walking in nature, meditation, yoga, sports activities, being with animals, giving care, and many more all have in common that they reduce stress. When stress is reduced then the inflammation and hypersensitivity reduces.

When a cycle of stress is building up then the only way to step on its brakes is to take a pause. That’s time for a pause with self-care.

Scientifically the best forms of self-care are oxytocin related. Let’s sum up some scientific facts.

- Oxytocin actually inhibits the hormone that weakens the antibodies that cause inflammatory reactions in “fear circuit areas” of the brain!

- Oxytocin makes us feel safe.

- Oxytocin boost social intelligence.

- Oxytocin increases the face perception and processing.

- Oxytocin reduces the amygdala’s responses to threatening social stimuli.

- Oxytocin brings us to the present moment of our felt experience while the amygdala brings us to the present moment of the perceived experience, where they cohere.

We can see that oxytocin and the amygdala work perfectly together. The amygdala has the role of keeping us safe while oxytocin makes us feel safe. When an autistic person feels safe then he or she can relax and come to him or herself without being over-sensitized.

Oxytocin, where to get it

Oxytocin is found to heal the amygdala and improve its social functions. There have been studies on Autism where oxytocin was administered, but the administration didn’t have a full effect because it didn’t stimulate the brain in the regions associated with reward and reinforcement.

Oxytocin is also called the trust hormone. When we trust then we feel safe. That kind of trust is a bond in which we see deep values that release more oxytocin creating a safe space with friends, family or partner. So by bonding with someone that is on the autism spectrum and caring for that bond will bring both together. Even when there is some accusation or guilt playing, sitting on the couch together hand in hand resolves much more then hours of arguments.

When we have trust then we have a base to heal on but for that trust to be really there the oxytocin needs to get flowing. Oxytocin is also connected to monogamy, protecting and caring for what is dear. It is found to change our outlook on things from negative to positive which helps us to find positive solutions. Oxytocin is also found to change and shape our social perception and it even makes us physically look more robust and trustworthy and attractive.

No one needs to look far for oxytocin. Oxytocin is readily available. We release oxytocin when we are generous, when we give care to something or someone, when we share a meal or a drink, when we walk outside, when we do a work out, when we are with good friends, when we meditate, when we do yoga, when we pet an animal, when we walk in nature, when we really observe something that fascinates us, when we hug or kiss, when we smile, when we do something we love doing, when we are being generous, when we are with equals, when we compliment someone, when we receive a compliment, when we play an instrument, when we make art and of course when we have loving sexual intercourse.

Oxytocin is a hormone that is found to flow more and more easily over time. This means that its effect gets amplified the more it is experienced. Autistics that have trouble with finding the right words in social situations can suddenly speak more fluently when there is a space where they feel safe. Like everyone, autistic people also become open when the social situation is pleasant and relaxed. Oxytocin also turns small-talk (which is basically just a set of amygdala responses for non-autistics) into a real-talk, where a-typical and neurotypical people can effortlessly connect and deepen the connection to meaningful levels.

Oxytocin is readily available in many situations. Some situations release more oxytocin, like for women when their nipples are stimulated, for men while they orgasm with someone they love, for woman during childbirth, during kissing, during hugging, during “looking each other in the eyes”. It also is released when we are looking at something or at someone we find beautiful, we release it with anything we really connect in, like in special interests, love and friendships. We can also feel its effect when we read something heartwarming and beautiful. That can also press our oxytocin button like maybe this part of the article.

Oxytocin is also found to work at its strongest when we stay away from too much social media, which in excess is detrimental to it, no matter the kitten and puppy pictures. It gets released by real bonds with family, friends, animals and nature in real-time. It is everywhere that we feel safe and happy which is always the place where we can heal.

Another important oxytocin producer that should me mentioned is the sun. The sun, or being out in daylight, has a positive impact on our oxytocin production and on stress reduction. At the same time our amygdala is healthily focused when we are in touch with nature. This helps to lower stress levels and brings the ability to cope better with sensitivity. Everyone feels better after some time outside. This counts even more for people that have autism.

There are many articles about getting autistic children outside. But the positive effect of sun and nature shouldn’t be overlooked for adults either.

Conclusion

There is actually a lot more to tell about these two almond shaped sets of neurons but this should suffice. Understanding the amygdala can make it easier for people on the autistic spectrum to cope better with their autism. When you know your autism then you can use your autism and turn it into your super power instead of that you are being lived by stress-loops. It is mainly for you that I wrote this article. But I hope that it also will help those that have someone near with autism. That they can understand better why people on the autism spectrum sometimes react as they do and how that is always an involuntary outcome circumstances that hardly ever are personal.

I hope that this article will bring people on the spectrum and not on the spectrum closer together through a deeper understanding and of course through a lot of oxytocin that is abundantly shared.

Some links to articles (references)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Limbic_system

https://iancommunity.org/anxiety-amygdala-autism

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3183515/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6321616/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5146198/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28285187

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/318340.php#1

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/03/190311133105.htm

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6598425/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4717322/

https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/10852/50999/Tanggaard.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17405629.2010.492000

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3598557/

https://www.livescience.com/35586-autism-brain-activity-regions-perception.html

https://cosolargy.org/sunlight-oxytocin-and-orexin/

https://jneuroinflammation.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12974-017-0981-8

I found this information very informative and simple to understand. My son had a late diagnosis with high functioning autism at the age of 36, he’s 43 now and has struggled with anxiety throughout his life.